From a Tent in Gaza: "Don't Look Away, Your Silence Is a Choice!"

While caring for her injured father amid Gaza's winter floods and ongoing siege, 22-year-old Sara Serria demands the world pay attention.

Today, I write from a tent amid winter storms and floods in Mawasi Khan Younis, Gaza —a tent that does not know me, that looks nothing like my pink room.

My name is Sara Serria. I am 22-years old, about to graduate with a degree in English translation from the Islamic University of Gaza. I was born and raised in Shuja’iyya.

And I write about a home that no longer exists, yet still lives inside me. About a neighbourhood we are forbidden to return to, even though the bombing has stopped. All we want is to see the rubble. To touch the memory. To say, “We were here.”

I write about my father, whose leg was shattered because he longed to see his land. About Khaled and Hashem, who died trying to feed their family. About a mother who lost everything. About neighbours who still dream of going back. I write about Shuja’iyya—not as a destroyed place, but as a full life, a memory, an identity, a love that refuses to die.

On the morning of Eid al-Fitr, April 1, 2025, we woke up to a silence that felt heavier than any bomb. There were no decorations, no scent of ma’amoul wafting through the neighbourhood, no children’s laughter echoing outside.

Still, I put on the dress I had saved for this day—a soft, sky-blue one I had chosen months ago, hoping to wear it when my brother returned home after eleven months in Israeli prison. He was finally with us. Thinner, quieter, but home. Now he sits beside me as I write this, and that alone feels like a miracle.

We gathered for Eid prayer, our hearts heavy with grief, our eyes scanning the sky for mercy.

But minutes after the final takbeer, the sky cracked open with the roar of an Apache helicopter. Its thunder shook the ground beneath us and sent a chill through our bones. We saw it circling above, then watched in horror as it fired on our neighbour’s home—Abu Issam’s house, already charred and broken since it was bombed in January 2024.

There was nowhere to run. The only space left intact in our home was a small room pressed against the neighbour’s wall. It had two standing walls and a slanted roof—barely a room, but it was all we had.

We huddled in its corner—my father, mother, brother, sister, and I—stacked atop one another, gripping hands, whispering the shahada, our hearts pounding like war drums. Shrapnel rained down. Dust filled the air. We could not see. We could not breathe. We waited for death to choose one of us.

People ran toward the smoke. Screams echoed.

Waseem, just 18 years old and the grandson of Abu Issam, staggered into view, blood streaming from his arm.

“My hand! My hand is gone!” he cried.

Behind him, his mother screamed, her voice shaking: “Do not be scared, habibi! Do not be scared!”

Waseem had already lost his father earlier that year—he had gone to fetch aid near the Kuwaiti roundabout and never came back.

On Eid, Waseem was bleeding and screaming in pain.

When the noise finally faded, we fled. No time to look back. No time to say goodbye. We ran to my aunt Om Ahmed’s house in the Shaaf neighbourhood. Deep down, we knew—we would not return soon.

I grew up in Shuja’iyya, a place unlike any other. Life pulsed through its streets. Our home, with its white stone front wall and the tiny garden my father tended with his bare hands, was our sanctuary.

My room—painted soft pink, with sheer curtains that danced in the breeze—was my world. On the wooden desk my uncle gifted me for graduating high school, I wrote dreams, studied late into the night, and imagined a future that now feels like fiction.

In Shuja’iyya, neighbours were family. We shared food, joy, grief, and every celebration. Every Friday, we gathered around one table, laughing, singing, telling stories.

On Eid, the streets came alive with children in new clothes, vibrant decorations, and the sweet aroma of desserts. We visited relatives, exchanged sweets, sipped coffee, and dreamed of better days.

Then the war came—and STOLE everything.

Since the genocide resumed on March 18, we have been trapped in a cycle of displacement. We have fled five times: from al-Shaaf to al-Rimal, to al-Nasr, to Gaza’s port, and finally to Mawasi Khan Younis. We walked for six hours under the scorching sun, carrying what little we had left.

Every time we tried to settle, to breathe, to reclaim normalcy, new warnings forced us to flee again. Stability became a myth. We lived on the edge of fear.

Mawasi Khan Younis is not our home. It does not know us, and we do not know it. The air is foreign. The neighbours are strangers. The tent we now live in offers no shelter from winter’s bite or summer’s blaze. Insects swarm our bodies. The place is cut off from the world, as if we have been exiled to the margins of existence. No electricity. No clean water. No privacy. No safety. Just waiting—waiting to return.

On June 14, my father tried to go back to Shuja’iyya. He was not carrying a weapon—only a heart full of longing. He wanted to see our home, even if it was just rubble. He left at dawn with his friend and neighbour, Kanaan. But a drone was watching. It fired two bullets—one struck his leg, the other his back. Kanaan, unharmed, carried him on his back all the way from Shuja’iyya to Al-Ma’madani Hospital.

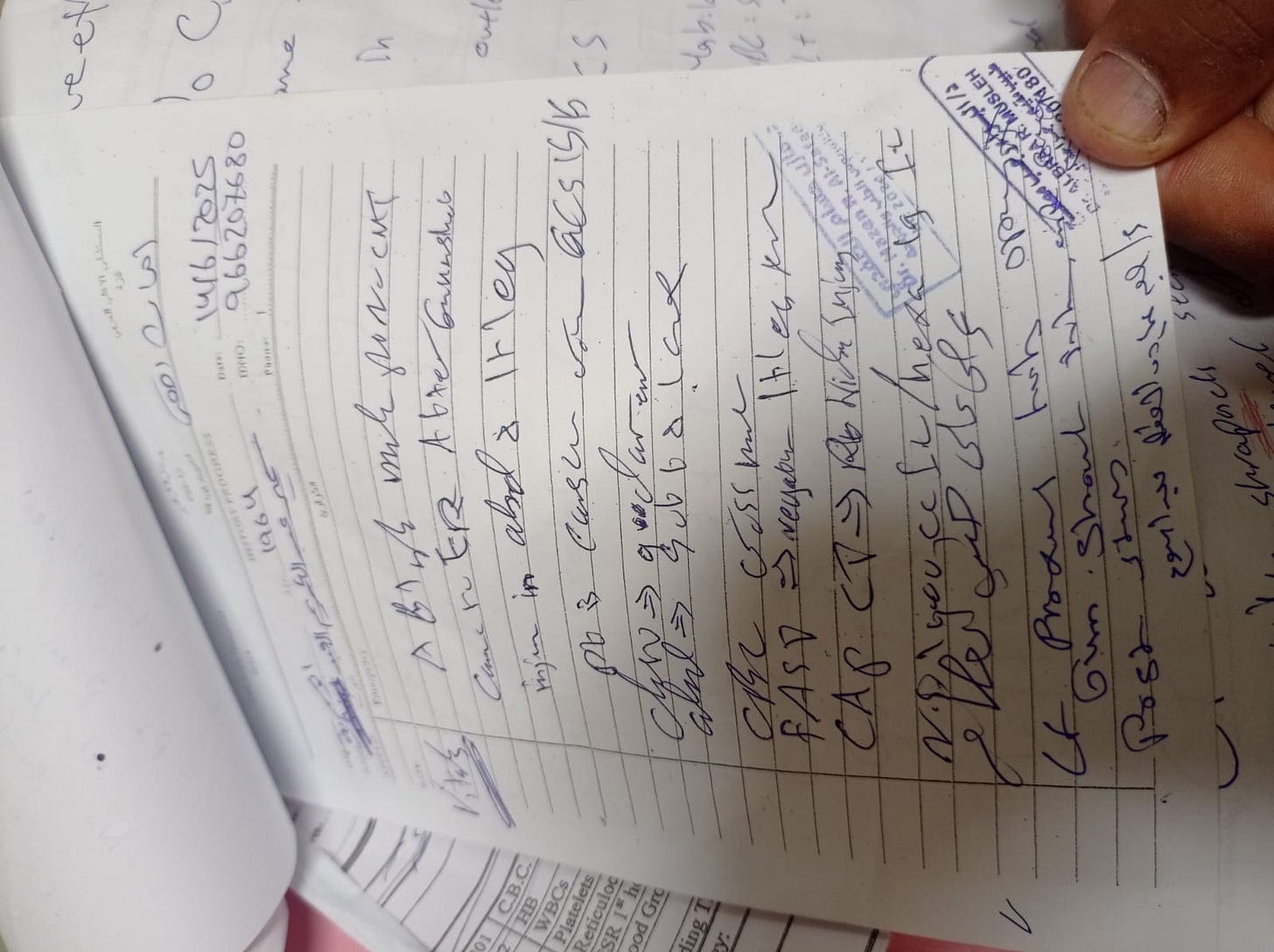

Now, my father walks with crutches. His leg is broken. His back is riddled with shrapnel. We have a medical report diagnosing him with a war injury, but no document can capture the depth of his pain—or ours.

In August, two young men from our neighbourhood—Khaled and Hashem al-Mamlouk, both in their twenties—were killed while trying to retrieve flour and a few essentials from their home.

Their sister, Doaa, who was widowed during the war, told us their mother has not spoken since. She does not eat. She does not drink. She just sits, whispering the same words over and over: “If only one of them had survived… just one.” She lost her husband and two sons. Now, she has no one left.

Their house still stood. That’s why they went back. They thought they could salvage something—anything. But even that small hope cost them their lives.

Our neighbour Abu Muhammad, 45, says, “I was born in Shuja’iyya. I grew up there. My children grew up there. The occupation destroyed our homes, our belongings—but it could not destroy our bond with this place. We will pitch our tents on the rubble if we have to. We won’t leave. We won’t let go.”

And Sabah, Om Fadi, our neighbour whose three sons were arrested at the start of the war, tells me, “Shuja’iyya is not just a neighbourhood. It is a piece of our soul. Its worth is the same as our children’s. How can they expect us to forget it? To abandon it?”

So tell me—

How can a person be forbidden from returning to their home, even when it is just rubble? How can someone be denied the right to stand on the soil of their childhood? How can longing become a crime? What law in this world forbids us from loving our homes? What logic deems ruins more dangerous than bombs? What kind of humanity stays silent while we are banned from going back?

Tell me…

Why Can’t We Go Home to Shuja’iyya?

Sara Serria, 22, is an English translation student from Gaza. She hopes to earn a scholarship to pursue a master’s degree abroad and be a voice for her people.

Hi Sara! It is beyond belief that the world leaders are just letting Israel carry on with this extreme cruelty to their own species. It shows up the evil nature of mankind. I pray that your suffering will end soon and this madness will end.

Thanks very much for sharing my piece. Grateful for the space to tell this story, and for everyone taking the time to read it.♥️